0. Introduction

Atheism may be defined provisionally as the view according to which there are no gods. However, despite this seemingly simple idea, there is a bit of controversy about the more precise meaning of ‘an atheist’. I will spell out some of the issues involved and outline my position.

- Atheism and theism

One might like to think of a proposition, p, which is to be understood as follows:

0) p = ‘Some god exists’

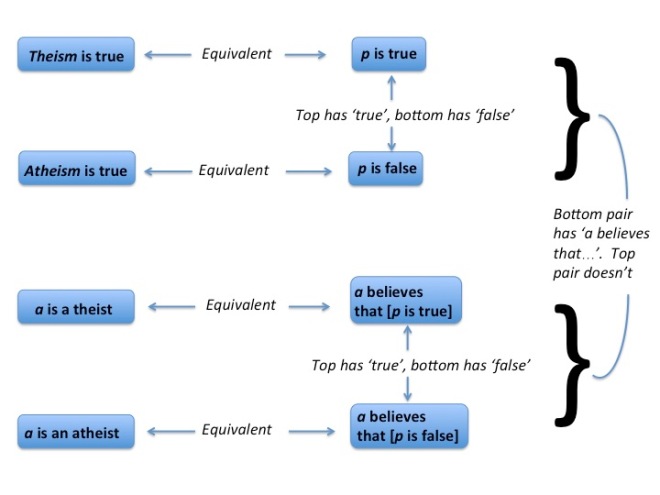

It seems clear that the terms ‘theism’ and ‘atheism’ have some intrinsic relationship to p. One may think that the relationship is of the following sort (where ‘iff’ means ‘if and only if’):

i) Theism is true iff p is true

ii) Atheism is true iff p is false

This means that theism is logically equivalent to the proposition that some god exists, and atheism is logically inequivalent to the proposition that some god exists (it is equivalent to the falsity of ‘some god exists’).

1.1 Atheist and theist

If we accept i) and ii) as the definitions of theism and atheism, then we may move on to the definition of ‘theist‘ and ‘atheist‘. Doing this means bringing the agent, a, into the definition. The natural way to define these terms is like this:

iii) a is a theist iff a believes that [p is true]

iv) a is an atheist iff a believes that [p is false]

There is a direct symmetry between -ism and -ist on this view. It is a nice and easy to grasp picture. The pattern is that the definiens of iii) and iv) are just those of i) and ii) but with the words ‘a believes that…’ at the start, and that the difference between theism/-ist and atheism/-ist is just that the former has ‘p is true’, and the latter has ‘p is false’. This means that a theist is just someone who believes that theism is true, and an atheist is just someone who believes that atheism is true. Thus, we have the pleasing result that theist is to theism what atheist is to atheism.

Here is a diagram of the logical relations:

If a is an atheist in the sense of iv) above, call her a ‘hard atheist‘.

2. Lacktheism

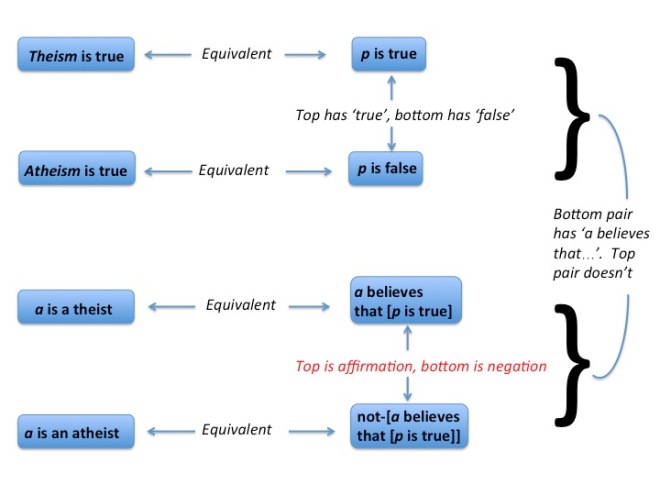

There is another way of characterising what it means to be an atheist, and this departs from the pattern we have established above. On this definition, an atheist is someone who does not believe that p is true:

v) a is an atheist iff not-[a believes that p is true]

This definition of atheism is well-represented in public defences of atheism. Atheists commonly claim not to have a positive belief that p is false, i.e. to believe that no god exists, but merely to lack the belief that p is true. When they are doing this, they are advocating v), and someone who does this is a ‘lacktheist’.

3. Does ‘atheist’ mean ‘hard atheist’ or ‘lacktheist’?

There is some controversy about whether ‘atheist’ means ‘hard-atheist’ or ‘lacktheist’. Often, ‘atheists’ self-describe as lacktheists, but this leads to a charge of being ad hoc by the theists. I will explain the controversy and why I think it is logically dissolvable. First, I will outline the argument by theists according to which an ‘atheist’ should be thought of as a ‘hard-atheist’.

It seems like v) (the definition of lacktheist) messes up with the symmetry we had between i) and iii) (theism and theist), and between ii) and iv) (atheism and atheist). The symmetry was that the difference between theism/-ist and atheism/-ist is that the former ascribes truth to p and the latter ascribes falsity to p. With definition v) in place of iv) though, we have switched to talking in terms of the negation of p instead. The diagram would look like this:

So, the theist is someone who believes that theism is true, but (according to v) the atheist isn’t someone who believes that atheism is true, rather they are someone who does not believe that theism is true. This seeming abnormality may be seen as reason to reject v) (lacktheist) in favour of iv) (hard-atheist). Why, we might think, should we break the symmetry? We might just insist that an atheist is to atheism as a theist is to theism. If so, then an ‘atheist’ is a hard atheist, and a lacktheist isn’t an atheist at all. Changing the definition of ‘atheist’ seems unsystematic. In this situation, it is not that atheist is to atheism what theist is to theism, so we have lost our intuitive looking principle.

Added to the feeling of oddity about breaking the symmetry of the definitions, theists may be cynical about the motives of the atheist who argues for v) rather than iv) (the lacktheist). The reason for this cynicism would be that a consequence of using v) is that the defender of it seems to have less burden of proof in an argument than the defender of iv). And a position with lighter burden is easier to defend. So, the theist may suspect the atheist is choosing definition v) over iv) for the sole reason that it makes her position easier to defend. If that were the only motivation on behalf of the atheist, we might view her decision to do so as ad hoc. In addition, if the approach treats atheist differently from any other similar position, then there could also be the accusation of special pleading as well.

The theist may insist that the situation should, in fact, be a level playing field, where each side (theist and atheist) has the same justificatory burden. The reasoning for this would be something like the following:

- If a says “I am a theist”, then a is implicitly saying that a believes that p is true.

- If a (even implicitly) says “I believe that p is true”, then a has the justificatory burden of the claim “p is true”.

- Therefore, if a says “I am a theist” then a has the justificatory burden of the claim “p is true”. (1, 2, hypothetical syllogism)

Thus, claiming to be a theist carries with it the justificatory burden of claiming that it is true that some god exists. These justificatory relations are mirrored with our first definition of an atheist:

- If a says “I am an atheist” (and means definition iv), then a is implicitly saying that a believes that p is false.

- If a (even implicitly) says “I believe that p is false”, then a has the justificatory burden of the claim “p is false”.

- Therefore, if a says “I am an atheist” this means that a has taken on the justificatory burden of the claim “p is false”. (1, 2, hypothetical syllogism)

Thus, if we use the original definition of ‘atheist’, then the theist and atheist have the same justificatory burden. Surely, to try to change the definition of atheism here would be just to avoid this burden.

And indeed, if a says “I am an atheist”, and means definition v), then a has not made an implicit claim about what a believes. Rather, a has made a claim that a does not have a belief that “p is true”. Thus, premise 1 above would be false if we used definition v) for ‘atheist’. This is why, if a uses the lacktheist definition of ‘atheist’, that a‘s claim “I am an atheist” does not have the justificatory burden of the claim that “p is false”, and why the burden is avoided.

So, the claim could be that the atheist is making an illegitimate switch, from iv) (‘hard atheist’) to v) (‘lacktheist’). It could be seen as illegitimate because definition v) seems to be an otherwise arbitrary breaking of the symmetry of definitions, and seems like it is only justified through the benefit it bestows on the defender of the position (which is the root of the ad hoc complaint). We shouldn’t treat the definition of atheism differently to theism unless there is a good reason to do so (or it would be special pleading). The atheist seems to have only selfish and illegitimate reasons for identifying as a lacktheist rather than as a hard-atheist.

4. Mirroring

However, one could in fact start the reasoning again slightly differently, and make ‘hard atheist’ look like the deviation from the pattern, and ‘lacktheist’ look like the expected one. This also transfers the charges of ad hoc and special pleading to the theist.

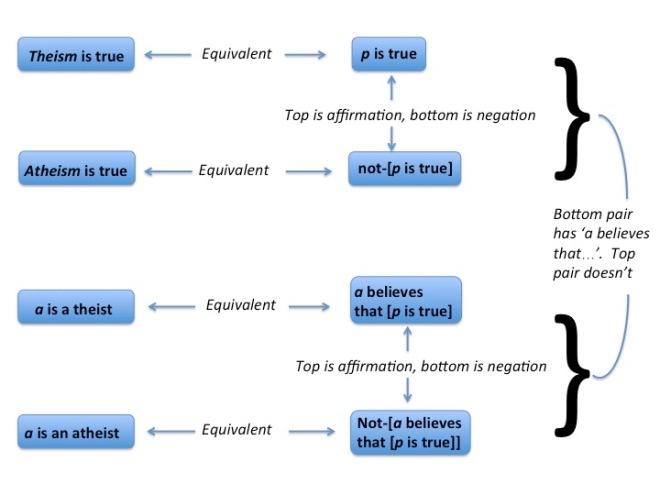

For example, we could stick with definition i), but define atheism as follows:

i) Theism is true iff p is true

vii) Atheism is true iff not-[p is true]

In a classical language, there would be nothing to distinguish between ii) and vii); ‘p is false’ is logically equivalent to ‘not-(p is true)’. Saying that atheism means that “it is not true that there are any gods”, seems just as faithful to the idea of atheism as the claim that it means that “‘there are gods’ is false”. Because they are equivalent, there is nothing one could appeal to logically which could decide in favour of i) rather than vii), and vice versa. Thus, we seem to have no real reason not to start from vii) if we want. And if we do proceed from here, then we can define theism as before, but use v) for the definition of atheism, and it looks like it is obeying the pattern of reasoning employed so far:

iii) a is a theist iff a believes that [p is true]

v) a is an atheist iff not-[a believes that [p is true]]

Now the relations between i) and iii), and vii) and v) are just as neat and tidy as they were earlier. Here is a diagram of the logical relations:

As before, the relation between -ism and -ist is just that the -ist definition has ‘a believes that…’ added before ‘p is true’. The relation between theism and theist on the one side and atheism and atheist on the other is just that the atheism/ist side has ‘not-…’ prefixing them. On this view, a theist is to theism what an atheist is to atheism. Note that v) is the definition of a lacktheist.

So, an atheist is ‘naturally’ thought of as a lacktheist if we say that atheism means that it is not true that some gods exist. Given that starting point, it isn’t changing the pattern of definitions to get to lacktheism; instead, it looks as if insisting on hard-atheism would be unsystematic here. One can imagine a theist insisting that an atheist should still be a hard-atheist , but this time the accusation of symmetry-breaking could be levelled at the theist for doing so. Who is being unsystematic, it seems, depends on the starting point taken.

And a theist would have a selfish motive for making this demand too. We cannot ignore the fact that insisting that the atheist breaks the symmetry and uses the definition of ‘hard-atheism’ would remove the justificatory advantage that the atheist would otherwise ‘naturally’ have. However, because ii) and vii) are logically equivalent, there can be no reason to pick one over the other, and so the insistence of the theist to use the hard-atheist definition looks to the atheist as being ad hoc – being done merely for the rhetorical benefit it provides to the theist.

Thus, the two positions mirror each other perfectly. Depending on the definition given for atheism, the definition of atheist as hard-atheist or lacktheist seems unwarranted. The theist judges the atheist as trying to illegitimately lighten their own burden; the atheist judges the theist as trying to illegitimately add to the atheist burden. Whether it makes the atheist’s job harder, or the theist’s job easier, depends on whether atheism means that it is false that some gods exist, or whether it is not that some gods exist is true. And there doesn’t seem like there could be any reason for picking one over the other.

There seemed to be an observation that atheist’s were making an illegitimate move when defining atheist as lacktheist, which was being done just to get an advantage over the theist rhetorically. But if we start at another position, it would seem like the theist is the one trying to shift the burden just for their own advantage. This seems to dissolve the accusations of foul play on either side.

5. Post-definitional thinking

I think that the lesson of all this is just that there is nothing purely logical to appeal to which means that ‘atheist’ should be thought of as ‘hard-atheist’ rather than ‘lacktheist’. Either view is equally defensible, and any choice between them can only be ad hoc. In a sense, as it is a discussion about the nature of definitions, it is rather pointless. And this is hardly surprising.

Instead of worrying about the definition of ‘atheist’, we should rather pay more attention to the nature of the beliefs that a holds. In addition to the basic notion of a simply believing that p, we can talk about the ‘degree of belief’ that a has that p. Let’s say that the degree of belief a has that p is the following:

Da(p) = x, where 0 ≤ x ≤ 1.

Degrees of belief are real numbers between 0 and 1, rather like probabilities. They express your feeling of confidence in a proposition. 0 is maximally uncertain, 1 is maximally certain, and 0.5 is absolute indecision.

It seems to me that the proposition p, that there are any gods, is rather hard to evaluate. I find the idea of a personal loving agent quite unlikely indeed, for various reasons (it seems suspiciously like the sort of thing made up by humans, for one). However, the question of whether there are any gods seems a lot more of a difficult thing to evaluate. Perhaps some kind of being created the universe, but remains utterly divorced from the subsequent comings and goings of the world itself, or perhaps one is fascinated by the comings and goings of radically different forms of life on the other side of the universe than us, etc. These sorts of ideas are interesting, but are almost impossible to say anything about, either for or against. I kind of couldn’t have any good reasons to think that any of these sorts of hypotheses were true rather than false. What would count as evidence for or against? In this situation, my degree of belief that p (i.e. the proposition ‘some god exists’) has got to be around 0.5.

Yet, I do have a sneaking suspicion that there probably aren’t any gods like this. If you put a gun to my head and made me decide, I would opt for the no-gods option. That’s what I think is more likely, and so I my degree of belief that p isn’t exactly 0.5. The following is certainly true:

Da(p) < Da(~p)

However, the imbalance seems to me to be very, very slight. I wouldn’t know how to put a precise number on it, but it seems reasonable to think that my degree of belief that ~p is between 0.5 and 0.55.

Now, does this state of mind mean that I believe that p? I certainly believe that there is an almost even probability about whether there are any gods or not, with a very slight imbalance towards no gods. My degree of belief is similarly minimally slanted towards the no-gods position. The question is the relation of these facts to the question of whether I believe that p.

Belief, as opposed to degree of belief, is an all or nothing notion. You either believe p or you don’t. Yet, my degree of belief is a scale. It ranges from 0 (definitely not belief) to 1 (definitely belief), and could be any value in between. How do the two notions relate to one another?

One idea, at one point seemingly advocated by William Lane Craig, is that the relation between belief and degree of belief is as follows:

“If it is more plausible that a premiss is, in light of the evidence, true rather than false, then we should believe the premiss.” (taken from: http://www.reasonablefaith.org/apologetics-arguments#ixzz4Kp11AOyR)

The idea could be put as follows:

a believes that p iff Da(p) > 0.5

So long as your degree of belief that p is more than 0.5, then you believe that p is true. On this view, saying that you ‘believe that p‘ just means that your degree of belief is more than 0.5.

One problem with this view is that there seem to be situations in which it sounds wrong to say ‘I believe that p‘, even though they are clearly situations where our degree of belief that p is more than 0.5. Here is one.

Say I have a pack of cards, I thoroughly shuffle it and I take one out. It is the ace of spades. I discard the card, and take another one without looking at it. Let r be the proposition that ‘the card is red’. Do I believe r?

The probability that r is true should be calculated as 26:51 (i.e., the remaining number of red cards:the remaining number of cards), or roughly 0.52. Given that I know this, my degree of belief that r is true should be correspondingly 0.52. Any other number would be perverse.

I think that in this situation, though my degree of belief is clearly in favour of red over black (or not-red), I still don’t think it is correct to say that I believe that the card will be red. I am sufficiently hesitant that the phrase ‘I believe that r is true’ would be misleading. It would indicate a higher degree of belief than that.

Perhaps you are thinking that you do believe that the card is red in this situation. Perhaps tilting the degree of belief 2 percentage points towards r is enough for you. If so, then consider the following version of the previous example:

Say I have a million packs of cards, I thoroughly shuffle it (somehow!) and I take one card out. It is the ace of spades. I discard the card, and take another one without looking at it. Let r be the proposition that ‘the card is red’. Do I believe r?

This situation is exactly like the previous one, except that the chance that the card is red is slightly closer to being exactly 50:50 than before. The probability would be: 0.50000002. Now, the chance that the card is red is only two millionths of a percentage point more likely than that it won’t be. Do you believe that it is red? If so, then your position is probably that of Craig’s above. Any imbalance in one direction entails belief rather than disbelief.

On the other hand, you may be agreeing with my intuition that asserting belief in these situations is incorrect. If so, then this means that there is some value of degree of belief (say 0.45 – 0.55 or something) in which is is not true that you believe p or disbelieve it (or believe ~p). In this penumbra (or indeterminate area) we lack belief that p, even though we possess a positive degree of belief that p. If you think this, then it cannot be true that ‘a believes that p iff Da(p) < 0.5′.

One may ask what the value is, if not 0.5? What does the value of your degree of belief that p have to be in order for it to be true that you believe that p? This, I think, is a complex question. One that is so complex, in fact, that it may be malformed. There may be no answer to it as such. It may be that in certain contexts the threshold is higher than others. Perhaps this varies from person to person, from conversation to conversation, from time to time, etc. Perhaps it varies in a chaotic and untraceable manner. This may be the case, within some sort of range outside of which it doesn’t go. For example, belief is never inappropriate in the case where the agent has a degree of belief which is 0.99, for example. It seems like it also isn’t appropriate in the case where the degree of belief is 0.50000001, etc. When people say ‘I believe that p‘, they are not necessarily reporting to a precise degree of belief (0.65 rather than 0.66, say), but just that they feel that their degree of belief is sufficiently over the threshold (whatever it is). Conversely, when someone says that they believe that ~p, this means that their degree of belief that ~p is sufficiently over the threshold (whatever it is) for ~p. When one is not sufficiently over either threshold, as in the card examples above, one should not say that one believes that p, or that one believes that ~p. One simply lacks beliefs in either direction. This is perfectly compatible with the idea that the degree of belief is believed, and perhaps even known. All that matters is that the degree of belief is extremely close to 0.5.

Thus, I have made a case for my claim to lack belief, which is not ad hoc because it is motivated by a general principle about when to withhold belief either way, and is not special pleading because I apply it to any case that is relevantly similar. I do not believe that any gods exist in the same way as that I do not believe that the card is red. In each case, my degree of belief is very close to 0.5, and that is what makes it inappropriate to affirm in either direction.

5. Conclusion

I think that this characterises my views about theism. I have a degree of belief that theism is false which is marginally over 0.5, but less than enough to indicate positive belief that it is false. Whether that counts as an atheist or not probably depends on your personal choice of definitions. Definitions aside, that is my view.

I think this is a reasonable approach. It resonates with my experience in deconstructing my religious beliefs – when I abandoned some of my positions that were based on biblical literalism, but conflicted with scientific and other evidence. The former consistency in my belief system was upset and I “went back to square one”. Looking for a starting point, I have yet to find a reason to push the belief needle very far in the positive direction. I’m probably actually somewhere below your self-assessment in fact.

It gave me some insight as well about how to think about the efforts by people on both sides to cast the burden of proof on the other side. I listen to apologetics and most of the time, for me, there is negligible effect on my confidence in the existence of god(s). Sometimes the arguments seem so poor, I go the other way on principle. “Bad form for Slytherin! You lose 50 points.”

One apparent typo in your post:

The idea could be put as follows:

a believes that p iff Da(p) 0.5″ instead. This is repeated later in the post.

LikeLike

I’m glad it resonated with you to some extent.

I’m not sure what you mean by the typo. Was it the ‘iff’?

LikeLike

I think there might be good reasons to break the “symmetry” in favor of “lacktheism.”

First, lack of belief is a perfectly reasonable doxastic position: lack of belief in p does not entail belief in not-p, and this could very well be the sincere position (belief) of the “lacktheist.” Absent a theist’s demonstration that either (a) lack of belief in p always entails belief in not-p (i.e., the lacktheist’s position is doxastically untenable) or that (b) the lacktheist’s position is ad-hoc for dishonest reasons (e.g., to gain unfair rhetorical advantages), the lacktheist is doxastically warranted in defending his position free from accusations of ad-hocness or insincerity (after all, the shoe could be on the other foot and the lacktheist could accuse the theist of dishonestly when the former accuses him of dishonesty for the same ad-hoc reasons).

Second, I contend that there is an inherent asymmetry in the evidential demonstrability of existence claims. Outside of a-priori “sciences” like mathematics or logic, and absent self-contradicting or inconsistent claims, proving non-existence is, essentially, impossible, while proving existence is eminently possible. Producing Russell’s teapot would complete the existence proof; not producing it would not constitute a non-existence proof.

In the physical world, in fact, a non-existence proof (barring self-contradicting claims such as violations of physical law, like perpetuum mobiles) is impossible. To prove that “something” or some “state of affairs” does not exist would require an observer to simultaneously gather information from all corners of the universe–a physical impossibility as it would require superluminal transfer of information.

Specifically in the theism/atheism case, I’m not claiming, nor do I need to claim, that God is only describable in the domain of the “evidential sciences,” but, rather, that to the extent that he/she/it is not exclusively describable by the a-priori “sciences” it may well be impossible to prove his/her/its non-existence. If it is impossible to prove the non-existence of a crafty, evasive Santa Claus, it may be no less impossible to prove God’s non-existence.

Lest a theist claim a gotcha! victory, let me remind the theist that this impossibility of non-existence proofs is not limited to God, but applies equally well to a potentially infinite number of fanciful concepts that most reasonable people don’t hold: pink flying unicorns, garden fairies, Big Foot, Leprechauns, the Loch Ness monster, invisible dragons in my garage, alien abductions, etc. etc. This “victory” would only place God squarely in the company of those same fanciful concepts.

To the extent that a theist does not forego evidential reasons for God’s existence, the asymmetry in the existence/non-existence proofs holds, I think.

This asymmetry would make an undue burden of proof on the “non-theist,” and would constitute an intellectually dishonest requirement by the theist, unless the non-theist claimed to be a “hard atheist.”

LikeLike

I believe this is solved when you consider the suffixs used – ‘ism’ and ‘ist’.

(1) ISM

The suffix ‘-ism’ when used about a theory or doctrine, as far as I am aware, describes the thing it is affirming. So in all cases I can think of ‘-ism’ words (and I’m willing to be corrected!), they do not have a corresponding ‘-ism’ word that simply denies the truth of what it claims.

For example, there isn’t ‘Marxism’ and then another ‘-ism’ that describes a theory that ‘Marxism’ is false. This seems obvious because someone would simply say “I don’t believe Marxism is true”, and so it would be redundant to have a new ‘-ism’ to describe this.

On these grounds, it seems to me like a view needs to affirm some theory or principle to count as an ‘-ism’ word, which is then either accepted or rejected. In other words, it seems to me like ‘-ism’ words cannot be contingent on other ‘-ism’ words.

For this reason, ‘atheism’ would more naturally mean the affirmation of the theory that there is no God, and the symmetry examples given in this article suggest an atheist is the proper name for someone who believes the theory of atheism, i.e. believes that there is no God.

(2) IST

For the atheist = lacktheist to be true (using Alex’s terms) then anything that ‘doesn’t believe it is true that God exists’ is an atheist… yes, anyTHING. By using the symmetry idea, all that is require is a lack of belief and hence all things that do not have a belief in God’s existence are Atheists. However, formal definitions of the ‘-ist’ suffix, and all other examples I can think of, require there to be, at the very least, a person. An ‘-ist’ is a person who holds an ‘-ism’. Surely this is the simplest, most consistent and obvious way to use these terms!

LikeLike

In response to your claim that ‘in the physical worlds proof of non-existence are impossible’…. not sure that is the case.

It may contradict itself, or contradict another better theory, or have evidence for it’s non existence. For example, I could believe there are no absolute morals (amoralism) and site as evidence that different cultures have different morals. Or general relativity claims there is no force of gravity by siting evidence that space-time is curved is a better theory that surplants the old one.

The point is, there can be an evidential case made that there is no God

LikeLike

I’m interested what you think happens if you include an action that is a result of a belief.

So, if the following argument is correct:

(1) if someone believes [a] then they would do [b]

(2) someone doesn’t do [b]

(3) therefore someone doesn’t believe [a]

In this case, your views on theism mean that you do not believe there exists any God that necessitates a certain action that you are not partaking in. Not simply that you lack belief in, but you believe it doesn’t exist.

I would suggest that Christianity and Islam are such Gods

LikeLike

Sorry – for clarification

let [a] be: ‘a God exists that demands a particular action that should be followed’

and [b] be: ‘the particular action demanded when able to’

LikeLike

I’ve had this sort of objection put to me elsewhere in relation to this. The argument is obviously valid. My reply is that premise 1 is false, so the argument isn’t sound.

Why do I say that premise 1 is false? Well, beliefs are compatible with lots of different behaviour. I used to smoke, and when I did so I knew full well that it caused cancer.

Let [a] be ‘smoking causes cancer’, and [b] be ‘stop smoking’. It would seem like anyone who believed that smoking caused cancer would stop smoking. Yet people don’t always act in this way to their beliefs. So even if I did believe p, I may still not act in accordance with p. This stops you being able to reason via modus tollens (as you did) from me not acting according to p to a belief that not-p.

Part of the problem is the conflict of other beliefs. I want to be happy, and i will be happy if I get fit, and I believe that going to the gym will make me fit. Yet I don’t go to the gym. I also believe that sitting on the sofa and eating chocolate will make me happy. So in the conflict of my beliefs, something has to give.

Maybe we always act in accordance with some belief or other, but in general you cannot reason from a particular act to a particular belief due to the inherent messy and complicated nature of our beliefs. Often we post hoc rationalise that our action was ‘because’ of a particular belief we hold, but in reality if we had acted in the opposite way we would have had a ready and waiting belief which we would claim was the ‘because’ for that action too. When I smoke it is because I believe it makes me look cool; when I give up it is because it will cause cancer. I believe both together. Etc, etc.

Hope that helps.

LikeLike

I think there is an extra step from ‘smoking causes cancer’ that would be something like (off the top of my head):

(1) if I believe ‘[a] = there exists a 100% reliable fortune-teller who tells me I’ll die tomorrow unless I never smoke again’ then ‘[b] = I will never smoke again’ [providing I am willing and able]

(2) I smoke again [though I am willing and able]

(3) I don’t believe such a fortune teller exists

LikeLike

I think that you can say that if you held a belief that there was that sort of fortune teller, than you would be very unlikely to keep on smoking, and that it would seem irrational to do so. However, there is no logical connection between having a belief like that and any particular action. There is no contradiction (that I can see) between believing that-p and acting in such a way that you do not believe that-p, for any p. I think I can just act against what I assess is the best thing to do, and sometimes do. It is called ‘akrasia’, or ‘weakness of will’ in the philosophy literature. These phenomena seem logically possible, anyway. And that is enough to prevent the argument from going through.

Anyway, even if somehow you were right, the argument would have to have a cateris paribus clause in there. I mean, maybe I believe that smoking now will kill me tomorrow with 100% certainty, and choose to smoke now as a way of avoiding the otherwise inevitable brain tumour I have just discovered that I have. Or maybe I have been captured by the Galactic Empire on charges of treason, and I smoke to avoid being tortured to death tomorrow afternoon. My point is that there would be circumstances where I have the belief you hold, and I do that action you think is linked to the belief, and it is a perfectly reasonable action because of extenuating circumstances. So for various reasons I don’t find your line of reasoning particularly plausible, even when patched up like you do.

LikeLike

Yes. I understand. So maybe the added conditionals will account for these?

(1) if ‘[a] = I believe there exists a 100% reliable fortune-teller who tells me I’ll die tomorrow unless I never smoke again’ and ‘[a1] I don’t want to die tomorrow’ and ‘[a2] I am willing and able to never smoke again’ then ‘[b] = I will never smoke again’

(2) I smoke again

(3) therefore either all or some of [a], [a1] or [a2] are not true.

In this ‘weakness of will’ is captured in [a2]?

It seems to me like there are some beliefs which will necessarily lead to actions given specific conditions. Maybe this is a bad example, but are you saying that you think there are no beliefs which necessarily lead to actions in some specific situations?

LikeLike

Well, I am not convinced there is any set of conditions like the ones that you outline that logically ensures that you will not do the action. No matter how much you strengthen your antecedent with more facts about my beliefs or motivations, this will never equal it being impossible for me to do the action in question. Motivations are just inherently non-determinative. They influence actions, and explain actions, but they do not determine actions. So both of my two types of counter-example still stand.

So, the first one is about possible circumstances in which the motivation becomes reasonable. Lets say that ‘[a] = I believe there exists a 100% reliable fortune-teller who tells me I’ll die tomorrow unless I never smoke again’ and ‘[a1] I don’t want to die tomorrow’ and ‘[a2] I am willing and able to never smoke again’. This doesn’t mean that I won’t smoke tomorrow. In the brain tumour example, I don’t want to die tomorrow, but I *really* don’t want to die in 6 weeks with the potentially painful and distressing consequences of the tumour. So even though I don’t want to die tomorrow, and I 100% know that smoking will kill me tomorrow, I do smoke, just to avoid the consequences of the tumour.

But even if there were no tumour-like thing I was avoiding, I think it is (at least) logically possible that I simply don’t act in accordance with my beliefs. Let’s suppose I am given 100% reliable information that smoking will kill me tomorrow, I fully believe that, and there are no extenuating circumstances like a tumour or torture, etc. I still say that I could (logically could) still smoke in that situation. Nothing really prevents me from doing so. Sure, I would be irrational. Sure, it makes no sense. But those constraints don’t actually stay my hand when it reaches for the cigarettes. I *could* still do so, even though I think it would be a terrible mistake. This seems pretty obvious to me if by ‘could’ we mean ‘is logically possible’. All that means is that there is no logical contradiction in supposing that it is true. It seems to me to be contradiction-free. If you think you can see a contradiction, please let me know what it is.

LikeLike

OK, I see what you say is write and the step from belief to action is (probably) non deterministic.

However, building on our conversation, you might agree the following is sound:

(1) If a rational person believes there exists [a] then they would do [b] unless [c] is true

(2) [d] is a rational person doesn’t do [b] and [c] is not true

(3) therefore [d] believes there does not exist [a]

In the smoking case it would be –

(1) If a rational person believes there exists [a 100% reliable fortune teller says you’ll die unless you stop smoking immediately] then they would [stop smoking immediately] unless [they wanted to die]

(2) You are a rational person who doesn’t [stop smoking immediately] and [you don’t want to die]

(3) Therefore you believe there does not exist [a 100% reliable fortune teller says you’ll die unless you stop smoking immediately]

The question I have with this is whether it is valid, or should (3) be: ‘therefore you do not believe there exists [a]?’

LikeLike

Well, whatever you do to strengthen the premises, I don’t think it will ever get around my second objection. Let’s say that I only have one desire (so that there is no mitigating circumstance, and so we can forget about my first objection). Let’s say this desire is to not die, and let’s say that I know with 100% certainty that if I do x then I will die. Does it follow logically that I will not do x? I don’t think it does.

You might object that if I was ‘rational’ then I wouldn’t do x. But my reply is that even if I am a rational person, it is still possible for me to act irrationally. Being rational is a de dicto property, not a de re property. To see the distinction, consider this. Is it possible for a ‘good mathematician’ to make a mistake in a simple addition? Well, if they did make such a mistake, then this makes the description of them as a ‘good mathematician’ less applicable to them; but there is nothing which logically prevents anyone from making a simple mistake in an addition. Even the best mathematician is fallible. So in a de dicto sense, a good mathematician cannot make a simple mistake, but only because the description would fail to hold of the person. In the de re sense, the actual person who is currently described correctly as a good mathematician could make a simple mistake. In the same way, even a perfectly rational person could (de re) do an irrational thing.

So I profoundly disagree with the basic idea of yours here, which is that actions logically indicate beliefs. In my view it is philosophically confused. It is often put forward in religious contexts, by people who are trying to make claims about what people believe which they cannot justify. It is based on a subtle, but perfectly dissolvable, confusion.

LikeLike

I believe this is solved when you consider the suffixs used – ‘ism’ and ‘ist’.

(1) ISM

The suffix ‘-ism’ when used about a theory or doctrine, as far as I am aware, describes the thing it is affirming. So in all cases I can think of ‘-ism’ words (and I’m willing to be corrected!), they do not have a corresponding ‘-ism’ word that simply denies the truth of what it claims.

For example, there isn’t ‘Marxism’ and then another ‘-ism’ that describes a theory that ‘Marxism’ is false. This seems obvious because someone would simply say “I don’t believe Marxism is true”, and so it would be redundant to have a new ‘-ism’ to describe this.

On these grounds, it seems to me like a view needs to affirm some theory or principle to count as an ‘-ism’ word, which is then either accepted or rejected. In other words, it seems to me like ‘-ism’ words cannot be contingent on other ‘-ism’ words.

For this reason, ‘atheism’ would more naturally mean the affirmation of the theory that there is no God, and the symmetry examples given in this article suggest an atheist is the proper name for someone who believes the theory of atheism, i.e. believes that there is no God.

(2) IST

For the atheist = lacktheist to be true (using Alex’s terms) then anything that ‘doesn’t believe it is true that God exists’ is an atheist… yes, anyTHING. By using the symmetry idea, all that is require is a lack of belief and hence all things that do not have a belief in God’s existence are Atheists. However, formal definitions of the ‘-ist’ suffix, and all other examples I can think of, require there to be, at the very least, a person. An ‘-ist’ is a person who holds an ‘-ism’. Surely this is the simplest, most consistent and obvious way to use these terms!

LikeLike

Slight correction on the second paragraph, it should read:

[For example, there isn’t ‘Marxism’ and then another ‘-ism’ that describes a theory that ‘Marxism’ is *not the case*. This seems obvious because someone would simply say “I don’t believe Marxism is true”, and so it would be redundant to have a new ‘-ism’ to describe this.]

Also – on reflection, I think ‘-ism’ words can actually be contingent on another ‘-ism’ words (e.g. may be Marxism entails Socialism), but they cannot be solely contingent on another ‘-ism’ word.

As another example, it would be completely redundant for me to define ‘Truemarxism’ as the theory the ‘Marxism’ is true. By reflection, it seems equally redundant for me to define ‘Nottruemarxism’ as the theory that ‘Marxism’ isn’t true.

LikeLike

This article has really been on my mind, so thank you Alex. This is because before reading this article I had always agreed with the modern usage of the term ‘atheist’ as being someone who doesn’t believe theism is true. I would identify as a theist myself, and have tended to go with the flow of the modern definition of atheist. But this article has really persuaded me otherwise for the reasons expressed above. I really am interested if you think that what I have said is legitimate and provides a strong case for the view that ‘atheism=there is no God’ and the mirror ‘atheist=believes there is no God’.

Another way I’ve been thinking about this is by comparison to a parallel I see. It seems to me what an ‘er’ is to an ‘ing’ when referring to an action is what an ‘ist’ is to an ‘ism’ when referring to a belief. So, an [x]er is someone who does the action of [x]ing; and likewise, an [x]ist is someone who believes the theory of [x]ism. Using this parallel, it’s easy to see that there must be some affirming content. When we think of an action, e.g. ‘running’, we obviously have a specific action in mind, something that is done by a ‘runner’. It seems obvious that we cannot describe ‘notrunning’ as an action noun itself, it doesn’t actually refer to anything other than running and so really the thing being referred to is ‘running’ (I think there are some parallels here to your objection to the theists refrain ‘nothing can come form nothing’ were ‘nothing’ is incorrectly used as a referent). I think we can see a parallel to this in the world of belief where the same pattern holds by simply substituting *action* with *theory* and *does* with *believes*:

A is someone who *does* the *action* of

A is someone who *believes* the *theory* of

By parallel, then, just as not [a]ing cannot be another action (when someone says they were not running they are not describing a new action called ‘notrunning’ but rather denying they were doing the action of running), similarly not [a]ism cannot be another belief.

To end on a lighter note, and illustrate the absurdity of this if I’m correct, if it’s true that *a is a p-ist = Not-[a believes that p is true]* (the second definition) then, as said previously, all things without the ability to believe are p-ists, which leaves us in the humorous situation that ‘theism is an atheist’.

LikeLike

The example should read:

A runner is someone who *does* the *action* of running

A capitalist is someone who *believes* the *theory* of capitilism

LikeLike

When you say that “it may contradict itself,” how so?

I think you slightly misquoted what I said because I was referring to physical reality, i.e., entities that exhibit physical properties. I was not referring to all non-existence proofs.

In plain language what I mean is that, *in general*, proofs of non-existence of objects that exhibit physical properties are not possible.

For example, suppose that I claimed that a life-size bust of my head (made of white marble, say), exists somewhere in the universe (not that anybody would want that, mind you :). Can you prove me wrong? The bust itself, if it existed, would not violate the “laws” of logic or of physics, etc. so in that sense you could not prove its non-existence through “obvious” inconsistencies or self-contradictions (like the proverbial married bachelor, for instance, or a perpetual motion machine).

So, barring self-contradictions, to prove the bust’s non-existence you’d have to have access to every nook and cranny of the universe *simultaneously*. But that, itself, is physically impossible (i.e., it would violate the laws of physics).

By contrast, a claim of existence could be easily proven by simply producing the bust.

In the realm of, say, mathematics, you can define the content of your universe and have simultaneous epistemic access to all elements in that universe, and be able to construct all manner of non-existence proofs like “there are no prime numbers between 7 and 11, exclusive” or “no eigenvalue of a stochastic matrix is greater than one” etc. The physical universe is fundamentally different.

In fact, the only “physical properties” that I require for my assertion is for the object in question (the bust) to “exist” in some generalized location in space and time within the physical universe, not be the physical universe itself, and be subject to the laws of physics (this last one is redundant with “exist within the physical universe”).

To see what I’m saying, denote the bust’s location “a” at some time “t1” as (a,t1). Suppose you claim that you checked that the bust is not in (b,t1). I could claim that it could well have been in (c,t1) all along, where c is spatially far away from b. By the time, t2, that you obtain information as to whether the bust was in (c,t1), it could well now be in some other location (d,t2), and so on.

The only way to resolve this, is for you to have information about all possible spatial locations a,b,c,d,e,… in the entire universe all at the same time. But this requirement, per Special Relativity is physically impossible, as it would require superluminal (i.e., faster-than-light) information transfer. This is not a technological obstacle, but an actual physical impossibility, much like a perpetual motion machine.

Now, I can see how a proposition about proofs that is self-referential may be self-refuting (the proposition may claim that its own proof is false), but I don’t see how that’s the case here, because I’m referring to the physical universe.

I’d be interested in finding a formulation of this problem that’s self-refuting

LikeLike

I understand what you’re saying and sorry for misquoting you. Regarding the physical world, what about proving that a ‘faster-than-the-speed-of-light bust of your head’ doesn’t exist? Just musing!

But back to the point of this article, I don’t really think ‘proof’ is the right term here anyway. Recall that this is about atheism, and whether it would be correct to call it a theory that no God exists. It seems to me in the case of other theories (or ‘ism’s) that the person who holds the view doesn’t have ‘proofs’ that the theory is true, but rather arguments that it should be held. E.g. If someone believes Marxism, they can never provide absolute definitive proofs that Marxism is right, but rather provide arguments that it is right.

So, as long as a person could provide arguments that there is no bust of you in the universe, then I can’t see why they couldn’t be justified in holding the theory that there is no bust of you in the universe (e.g. We do not know of one in existence, there is no good reason to believe that someone has made one, there is a low probability of one forming randomly, a bust of you is not a necessary thing etc. etc).

I think this all makes sense?

LikeLike

PS – what I mean by ‘it may contradict itself’ is that I can prove that a square circle doesn’t exist. So if a proposed being can be shown to be contradictory then you have proved that it cannot and therefore does not exist

LikeLike

No, I’m afraid that what you say doesn’t make any sense to me.

The point here was to decide whether existence and non-existence are “symmetric” claims when it comes to burden of proof (that’s how “proof” *is* relevant here :).

My position was that the burden of proof resides with the positive claim (existence) whenever the existence claim refers to an object that exhibits physical properties (EVEN IF it exhibits logical consistency AND it doesn’t violate physical law).

Your example of “Marxism is right” is not relevant because (a) Marxism is not an object that exhibits physical properties, and (b) the claim in your example is not about existence but about the interpretation of the concept of Marxism as being “right.” Apples and oranges here :).

Your “square circle doesn’t exist” example is not relevant either because it’s a logical contradiction which, if you read my post, does not apply to the object whose existence is being questioned, because I defined it as something that was logically consistent:

“…in that sense you could not prove its non-existence through “obvious” inconsistencies or self-contradictions (like the proverbial married bachelor, for instance, or a perpetual motion machine).” You could easily add a “square circle” or a “doughnut without a hole” etc. etc. These are irrelevant examples.

You claimed that you thought this could be self-contradicting. I’d love to see a demonstration of that.

LikeLike

I’m not sure the point was to see if ‘existence’ and ‘non-existence’ are symmetric.

Burden of proof lies with whoever makes a truth claim, surely?

My Marxism example was merely to show that you back up a theory with evidences, not proofs that provide certainty

In terms of the physical world – two points come to mind: (1) no-one claims God is physical so seems irrelevant anyway; (2) But also, I think you absolute can provide evidences that a physical object doesn’t exist. As I said with your ‘bust of you’ example, my evidences that it doesn’t exist may be [a] you don’t know of anyone who has made one, [b] there is no good reason for someone to make a bust, [c] the probability of one forming by chance is incredibly small, [d] it doesn’t seem a necessary object, etc.etc.

Maybe we’ll have to agree to disagree. I still feel convinced that the link between ‘Atheist’ and ‘Atheism’, and the need for an [x]ist to believe in [x]ism would favour the interpretation that Atheism=theory there is no God, otherwise everything in the universe that doesn’t have a belief in God’s existence (including objects that can’t believe) would be atheists!

LikeLike

The whole point of Alex’s article was to ascertain whether theism and atheism were “symmetrical” claims and whether “theist” or “atheist” had symmetrical burdens. I offered a reason why the burdens are not symmetrical, and why the theist has a larger burden of proof than the atheist.

“I’m not sure the point was to see if ‘existence’ and ‘non-existence’ are symmetric.”

–The point is that a theist makes a claim of belief in the “existence” (of at least one god), it’s that simple. I’m not sure what the problem is here?

“(1) no-one claims God is physical so seems irrelevant anyway;”

–But a theist god does interact with the physical world (alleged miracles, resurrections, plagues, floods, parted seas, talking donkeys, talking snakes, answered prayers, punishments, part-human/part-god entities, etc.). So to the extent that this God interacts with the physical world, he/she/it exhibits physical properties. Otherwise, we’d be talking about “deism.”

“(2) But also, I think you absolute[ly] can provide evidences that a physical object doesn’t exist.”

–Yes, but where did I dispute that? I was saying that the burden is much more onerous on someone who lacks belief, because non-existence is much harder to demonstrate than existence.

As to your examples of evidences that my marble bust doesn’t exist, they are all rather weak and indirect, especially when you compare them to my ability to prove my existence claim: I simply produce the darn thing–easy!

Here are your own examples:

“[a] you don’t know of anyone who has made one.”

–Why do you claim that? How can you be sure? I may know that someone has made one. You and I both know of many (many!) examples of busts that do exist (just go to a museum of classical art, say), so it’s not at all a stretch that one of me exists.

“[b] there is no good reason for someone to make a bust”

–Not at all! The fact that many busts exist means that people throughout history must have had reasons that are, well… good enough to make them!

“[c] the probability of one forming by chance is incredibly small”

–Yes, I agree, but I never claimed that it formed by chance, only that one of me exists. I made no claim of how it was made. So this objection is irrelevant.

“[d] it doesn’t seem a necessary object, etc.etc.”

–Yes, I agree, but I never claimed that it was a necessary object, etc. etc.

So, you see, you’re supporting my claim with your own examples: It’s VERY DIFFICULT for you to prove that something doesn’t exist, and VERY EASY for me to prove my claim that it does exist by simply pointing you to where it is. Hence the ASYMMETRY of the claims.

“Maybe we’ll have to agree to disagree.” Indeed.

“I still feel convinced that the link between ‘Atheist’ and ‘Atheism’, and the need for an [x]ist to believe in [x]ism would favour the interpretation that Atheism=theory there is no God,”

–What can I say, that’s your prerogative, of course. But I reject that atheism is a theory of anything or that an “atheist” has to have a theory of anything, anymore than a person who doesn’t accept assertions that fairies exist, must be committed to a theory of their non-existence, or anything at all.

Let me give you an example. If I toss a coin and cover it with my hand before you can see it, and ask you “Do you believe it’s heads?” You say “No.” Does that commit you to believing that it’s “tails”? Does that commit you to a theory that it’s “not heads”? I maintain that it doesn’t commit you to a belief nor to any theory.

In other words: NOT BELIEVING SOMETHING DOES NOT COMMIT YOU TO BELIEVING THE CONTRARY, NOR TO A THEORY OF THE CONTRARY, NOR TO A THEORY OF ANYTHING, FOR THAT MATTER.

“otherwise everything in the universe that doesn’t have a belief in God’s existence (including objects that can’t believe) would be atheists!”

–I’m not even sure this makes any sense at all :). I think the working presumption is that whomever does either the believing (the theist), or the withholding of belief because she doesn’t find the evidence compelling enough (the atheist), or believing the contrary (the hard atheist) should at least have the capability of forming beliefs! In either case, if you insist on calling inanimate objects “atheists,” because they lack beliefs, that’s your prerogative. It’s just a label. It doesn’t invalidate or add anything to the arguments here. You may as well call them “non-dentists” or “apathetic” also! 🙂

I think the disconnect here might come from how theists’ belief in their god is far more important to them than an atheist’s lack of belief is to her. If, as an atheist, you place lack of belief in a god in the same category as lack of belief in fairies, Leprechauns, world-creating pixies, ghosts, pink flying unicorns, and the like, none of these things are all that important to you. I.e., your “theories of the world” or whatever don’t depend strongly on whether you believe in pink flying unicorns, and you don’t have theories about the non-existence of pink flying unicorns. The same thing goes for gods, if you simply don’t believe in them.

The reason we don’t have labels such as “pink-flying-unicornists” vs. “a-pink-flying-unicornists” is because we don’t have pervasive beliefs in pink flying unicorns in our society today, so we don’t have a need for such labels.

Now, a theist may find god belief or lack of belief as something very fundamental to their (the theist’s) world and their views about the world, so they may want to insist that it should also be important for the atheist (which is not necessarily the case), and they may want to insist that lack of belief in the theist’s god is so earth-shattering and fundamental, that it should be part of the atheist’s “worldview” or something like that. In some sense, theists are “projecting” their own view onto atheists and placing unwarranted requirements on the atheists.

Cheers.

LikeLike

Hello Alex, I posted here as “Miguel” previously, but, when I tried to reply to someone’s comment, I had a problem with WordPress where I couldn’t login or retrieve my password, so I had to get another account. I couldn’t call myself “Miguel” anymore because, the name was “already in use” (probably by me :).

Anyway, I had to come up with another name and came up with this one. Just FYI. (And you don’t have to “approve” this post, as it’s just, er, FYI.)

Thanks.

LikeLike

I imaged you ending that post with a ‘so there!’ and sticking your tongue out.

Few things on what you said (my comments start with >)

“The whole point of Alex’s article was to ascertain whether theism and atheism were “symmetrical” claims and whether “theist” or “atheist” had symmetrical burdens”

> I don’t think it was, I thought the symmetry being discussed was between atheist and atheism compared with theist and theism. The burden question was a subsequent discussion

“I offered a reason why the burdens are not symmetrical, and why the theist has a larger burden of proof than the atheist.”

> That might be the case, but that’s irrelevant. We’re trying to get at meanings of words and consistency of language.

“I’m not sure the point was to see if ‘existence’ and ‘non-existence’ are symmetric.”

“(2) But also, I think you absolute[ly] can provide evidences that a physical object doesn’t exist.”

–Yes, but where did I dispute that? I was saying that the burden is much more onerous on someone who lacks belief, because non-existence is much harder to demonstrate than existence.

> So what? You can’t define what an ‘ism’ is based on how easy or hard the burden of proof is. That is entirely irrelevant.

“I still feel convinced that the link between ‘Atheist’ and ‘Atheism’, and the need for an [x]ist to believe in [x]ism would favour the interpretation that Atheism=theory there is no God,”

–What can I say, that’s your prerogative, of course. But I reject that atheism is a theory of anything or that an “atheist” has to have a theory of anything, anymore than a person who doesn’t accept assertions that fairies exist, must be committed to a theory of their non-existence, or anything at all.

> That’s fine, it’s fine for some one to not believe God exists, and therefore not be a theist, or reject theism. But this is a discussion of terminology. If atheism is a thing, then all other examlples of ‘isms’ affirm something, not merely deny another ‘ism’. As I said previously, this makes it redundant.

In other words: NOT BELIEVING SOMETHING DOES NOT COMMIT YOU TO BELIEVING THE CONTRARY, NOR TO A THEORY OF THE CONTRARY, NOR TO A THEORY OF ANYTHING, FOR THAT MATTER.

> I understand… You miss my point entirely. As I said, the article was asking ‘what is atheism’ which is a question about termonology. My only contention is that if we follow normal convention, atheism must be a theory about something. I understand that someone can just not believe in God without believing there is no God, but it seems obvious to me that they are simply not a theist. An atheist, however, believes atheism. That sentence makes no sense if atheism means not-theism.

“otherwise everything in the universe that doesn’t have a belief in God’s existence (including objects that can’t believe) would be atheists!”

–I’m not even sure this makes any sense at all :). I think the working presumption is that whomever does either the believing (the theist), or the withholding of belief because she doesn’t find the evidence compelling enough (the atheist), or believing the contrary (the hard atheist) should at least have the capability of forming beliefs! In either case, if you insist on calling inanimate objects “atheists,” because they lack beliefs, that’s your prerogative. It’s just a label. It doesn’t invalidate or add anything to the arguments here. You may as well call them “non-dentists” or “apathetic” also!

> You prove my point. A non-dentist is someome who is not a dentist, just as a not-theist is not a theist. This is different from an atheist.

I think the disconnect here might come from how theists’ belief in their god is far more important to them than an atheist’s lack of belief is to her. If, as an atheist, you place lack of belief in a god in the same category as lack of belief in fairies, Leprechauns, world-creating pixies, ghosts, pink flying unicorns, and the like, none of these things are all that important to you. I.e., your “theories of the world” or whatever don’t depend strongly on whether you believe in pink flying unicorns, and you don’t have theories about the non-existence of pink flying unicorns. The same thing goes for gods, if you simply don’t believe in them.

> No, the disconnect is that you have made a huge leap. I’m not saying someone should define themselves as anything. Somebody is not either a theist or an atheist. Someone may be neither. If someone does not believe in God they are just not a theist. The question is why is it so important for you to call yourself an atheist?

The reason we don’t have labels such as “pink-flying-unicornists” vs. “a-pink-flying-unicornists” is because we don’t have pervasive beliefs in pink flying unicorns in our society today, so we don’t have a need for such labels.

Now, a theist may find god belief or lack of belief as something very fundamental to their (the theist’s) world and their views about the world, so they may want to insist that it should also be important for the atheist (which is not necessarily the case), and they may want to insist that lack of belief in the theist’s god is so earth-shattering and fundamental, that it should be part of the atheist’s “worldview” or something like that. In some sense, theists are “projecting” their own view onto atheists and placing unwarranted requirements on the atheists.

> > Please look up the definition of the suffix ‘ism’ and ‘ist’. reading them should clear this up. It is not about unwarranted requirements, you clearly have a bee in your bonnet. It’s just about termonology. I leave you with a thought – If you lack belief in God why do YOU need the label atheist. Why not just that your not a theist?

Alex, fancy throwing in any of your clear headed logic here?

LikeLike

My comments are below start with (**).

I imaged you ending that post with a ‘so there!’ and sticking your tongue out.

(**)Aren’t we getting a little personal here? 🙂 I didn’t stick my tongue out, I thought I was very respectful, even if I argued my points passionately. Please, don’t be offended, it’s OK to disagree :).

Few things on what you said (my comments start with >)

“The whole point of Alex’s article was to ascertain whether theism and atheism were “symmetrical” claims and whether “theist” or “atheist” had symmetrical burdens”

> I don’t think it was, I thought the symmetry being discussed was between atheist and atheism compared with theist and theism. The burden question was a subsequent discussion

“I offered a reason why the burdens are not symmetrical, and why the theist has a larger burden of proof than the atheist.”

> That might be the case, but that’s irrelevant. We’re trying to get at meanings of words and consistency of language.

(**) I think it’s been a while since you last read Alex’s article. Allow me to quote a few paragraphs from Alex’s article, towards the end (emphasis with CAP LETTERS is my own):

———————————————–From Alex’s article: ————————-

So, an atheist is ‘naturally’ thought of as a lacktheist if we say that atheism means that it is not true that some gods exist. Given that starting point, it isn’t changing the pattern of definitions to get to lacktheism; instead, it looks as if insisting on hard-atheism would be unsystematic here. One can imagine a theist insisting that an atheist should still be a hard-atheist , but this time the accusation of SYMMETRY-BREAKING could be levelled at the theist for doing so. Who is being unsystematic, it seems, depends on the starting point taken.

And a theist would have a selfish motive for making this demand too. We cannot ignore the fact that insisting that the atheist breaks the SYMMETRY and uses the definition of ‘hard-atheism’ would remove the justificatory advantage that the atheist would otherwise ‘naturally’ have. However, because ii) and vii) are logically equivalent, there can be NO REASON TO PICK ONE OVER THE OTHER, and so the insistence of the theist to use the hard-atheist definition looks to the atheist as being ad hoc – being done merely for the rhetorical benefit it provides to the theist.

Thus, the two positions MIRROR EACH OTHER PERFECTLY. Depending on the definition given for atheism, the definition of atheist as hard-atheist or lacktheist seems UNWARRANTED. The theist judges the atheist as trying to illegitimately lighten their own BURDEN; the atheist judges the theist as trying to illegitimately add to the atheist burden. Whether it makes the atheist’s job HARDER, or the theist’s job EASIER, depends on whether atheism means that it is false that some gods exist, or whether it is not that some gods exist is true. And there doesn’t seem like there could be any reason for picking one over the other.

There seemed to be an observation that atheist’s were making an illegitimate move when defining atheist as lacktheist, which was being done just to get an advantage over the theist rhetorically. But if we start at another position, it would seem like the theist is the one trying to shift the BURDEN just for their own advantage. This seems to dissolve the accusations of foul play on either side.

5. Post-definitional thinking

I think that the lesson of all this is just that there is nothing purely LOGICAL to appeal to which means that ‘atheist’ should be thought of as ‘hard-atheist’ rather than ‘lacktheist’. Either view is EQUALLY DEFENSIBLE, and any choice between them can only be ad hoc. In a sense, as it is a discussion about the nature of definitions, it is rather POINTLESS. And this is hardly surprising.

Instead of worrying about the definition of ‘atheist’, WE SHOULD RATHER PAY MORE ATTENTION TO THE NATURE OF THE BELIEFS THAT a HOLDS. In addition to the basic notion of a simply believing that p, we can talk about the ‘degree of belief’ that a has that p. Let’s say that the degree of belief a has that p is the following: [….]

————————————————————————End of Alex’s quote.——————-

(**) You can see that the point of the article was to decide to what extent the the labels should be “symmetric” (Alex’s term) or whether there’s justification for “breaking the symmetry” (Alex’s term) by appealing to different “burdens” (Alex’s term) and that we can attempt to do this by paying attention to the nature of the beliefs. I attempted to provide a reason (a warrant) as to why they should not be symmetric, because of the undue burden required of the person who’s supposed to defend “non-existence.”

“I’m not sure the point was to see if ‘existence’ and ‘non-existence’ are symmetric.”

“(2) But also, I think you absolute[ly] can provide evidences that a physical object doesn’t exist.”

–Yes, but where did I dispute that? I was saying that the burden is much more onerous on someone who lacks belief, because non-existence is much harder to demonstrate than existence.

> So what? You can’t define what an ‘ism’ is based on how easy or hard the burden of proof is. That is entirely irrelevant.

(**) I was addressing your point (2), so if there’s a “so what?” it applies to your comment (2). Your point (2) was not talking about definitions of an ‘ism’ but whether it’s possible to provide evidences that a physical object doesn’t exist, which in turn missed my original point. We’re really talking past each other at this point.

“I still feel convinced that the link between ‘Atheist’ and ‘Atheism’, and the need for an [x]ist to believe in [x]ism would favour the interpretation that Atheism=theory there is no God,”

–What can I say, that’s your prerogative, of course. But I reject that atheism is a theory of anything or that an “atheist” has to have a theory of anything, anymore than a person who doesn’t accept assertions that fairies exist, must be committed to a theory of their non-existence, or anything at all.

> That’s fine, it’s fine for some one to not believe God exists, and therefore not be a theist, or reject theism. But this is a discussion of terminology. If atheism is a thing, then all other examlples of ‘isms’ affirm something, not merely deny another ‘ism’. As I said previously, this makes it redundant.

(**) OK, I’m glad we agree on something. I’m not sure that “atheism is a thing” (define “thing”), but in any case, let’s assume for the sake of argument, that all other ‘isms’ affirm something (you’ve used “Marxism” in your examples before), rather than deny something else. With your example, “Marxism” would not be the “denial of Capitalism” or something like that. I would agree with you. However, you seem to be focusing only on the suffix “ism” while completely ignoring the PREFIX “a” which means “free or without, or the absence of,” and its meaning is similar to the suffix “less.” In that case, the closest to someone who does not subscribe to Marxism is not “Capitalist” but rather “a-Marxist.” Of course, we don’t have such a term. But we do have the terms a-theism and a-theist. and the whole point of Alex’s article is whether we should think of an atheist as someone who’s a hard atheist or a “lacktheist,” and under what situations it would be warranted to say than an “atheist” is a “lacktheist” or a “hard atheist.”

In other words: NOT BELIEVING SOMETHING DOES NOT COMMIT YOU TO BELIEVING THE CONTRARY, NOR TO A THEORY OF THE CONTRARY, NOR TO A THEORY OF ANYTHING, FOR THAT MATTER.

> I understand… You miss my point entirely. As I said, the article was asking ‘what is atheism’ which is a question about termonology. My only contention is that if we follow normal convention, atheism must be a theory about something. I understand that someone can just not believe in God without believing there is no God, but it seems obvious to me that they are simply not a theist. An atheist, however, believes atheism. That sentence makes no sense if atheism means not-theism.

(**) We’re here trying to decide which of the two definitions (soft or hard atheist) apply to atheist. Again, I fail to see that it should be the “hard” variety, because of the prefix “a” which means, literally, “THE ABSENCE OF.” In this case, that could definitely be interpreted as someone who lacks theism, without being committed to any theory or belief! Alex was contending that either the “weak” or the “strong” form could apply. I provided reasons for why I believe the meaning should be the “weak” form of atheism (“lacktheism”) because of the asymmetry in the burden of proof, which was not expounded upon by Alex in his article.

“otherwise everything in the universe that doesn’t have a belief in God’s existence (including objects that can’t believe) would be atheists!”

–I’m not even sure this makes any sense at all :). I think the working presumption is that whomever does either the believing (the theist), or the withholding of belief because she doesn’t find the evidence compelling enough (the atheist), or believing the contrary (the hard atheist) should at least have the capability of forming beliefs! In either case, if you insist on calling inanimate objects “atheists,” because they lack beliefs, that’s your prerogative. It’s just a label. It doesn’t invalidate or add anything to the arguments here. You may as well call them “non-dentists” or “apathetic” also!

> You prove my point. A non-dentist is someome who is not a dentist, just as a not-theist is not a theist. This is different from an atheist.

(**) Yes a non-dentist is someone who’s not a dentist but every inanimate object would also fit that description, according to YOUR definition because you would insist that non-dentist means not being a dentist, which fit inanimate objects. Remember, it was you who brought inanimate objects here, not me. Yes, you could probably say that a “not-theist” is not a theist, but not being a theist does not entail that you believe anything!!! It simply means that you do not subscribe to the beliefs of a theist. You’re insisting that “not a theist” is different from “atheist.” I completely disagree. Look up the definition of the suffix “a.” If that doesn’t do it for you, please note that this is precisely what we are trying to argue here. You can’t simply assert your conclusion without supporting it. Again, we’re talking past each other.

I think the disconnect here might come from how theists’ belief in their god is far more important to them than an atheist’s lack of belief is to her. If, as an atheist, you place lack of belief in a god in the same category as lack of belief in fairies, Leprechauns, world-creating pixies, ghosts, pink flying unicorns, and the like, none of these things are all that important to you. I.e., your “theories of the world” or whatever don’t depend strongly on whether you believe in pink flying unicorns, and you don’t have theories about the non-existence of pink flying unicorns. The same thing goes for gods, if you simply don’t believe in them.

> No, the disconnect is that you have made a huge leap. I’m not saying someone should define themselves as anything. Somebody is not either a theist or an atheist. Someone may be neither. If someone does not believe in God they are just not a theist. The question is why is it so important for you to call yourself an atheist?

(**) I don’t agree that someone can be neither a theist nor an atheist. If these are defined as belief and lack of belief (in a god), there’s no middle ground: you are either convinced or not convinced and these cover all possibilities (by the Law of the Excluded Middle). Yes, they are not a theist if they don’t believe in God (they are an a-theist, which means they lack (absence of) belief. Again, if “theist” means someone who believes in a god, “atheist” means someone who lacks a belief in a god (or who does not have a theory on the existence of God). This is precisely what the Greek suffix “a” stands for. I never said it was “important” for me to “call myself an atheist,” my friend. You’re putting words in my mouth; I’m simply debating (hopefully in a cordial way) why I believe theists may want to impose a higher burden on atheists by requiring atheists to “believe” in something or “have a theory of” something. Again getting personal? 🙂

The reason we don’t have labels such as “pink-flying-unicornists” vs. “a-pink-flying-unicornists” is because we don’t have pervasive beliefs in pink flying unicorns in our society today, so we don’t have a need for such labels.

Now, a theist may find god belief or lack of belief as something very fundamental to their (the theist’s) world and their views about the world, so they may want to insist that it should also be important for the atheist (which is not necessarily the case), and they may want to insist that lack of belief in the theist’s god is so earth-shattering and fundamental, that it should be part of the atheist’s “worldview” or something like that. In some sense, theists are “projecting” their own view onto atheists and placing unwarranted requirements on the atheists.

> > Please look up the definition of the suffix ‘ism’ and ‘ist’. reading them should clear this up. It is not about unwarranted requirements, you clearly have a bee in your bonnet. It’s just about termonology. I leave you with a thought – If you lack belief in God why do YOU need the label atheist. Why not just that your not a theist?

(**) If it’s all about terminology, then PLEASE LOOK UP THE DEFINITION OF THE PREFIX “A” which should help clear some of this up. I offered the “unwarranted requirements” argument as a way to “break the symmetry” (this is Alex’s own terminology, not mine) and to show that the “lacktheist” was a more appropriate definition for “atheist” than “hard atheist.”

(**) Again, Alex argued in his article that either definition (“strong” or “weak”) can be thought of as valid. I gave reasons, including the asymmetry in the burden of proof, to show that “weak” was preferred. You keep bringing up the “ism” and “ist” suffixes, while ignoring the “a” prefix, which also has a meaning!

(**) Again, I don’t have, nor have I expressed, a “need” for any labels, it is YOU who want to label me that way. I’m simply attempting to argue on the merits; my personal beliefs or lack thereof is of no concern. And yes, not being a theist, is the same as being an atheist.

(**) As for the “bee in my bonnet,” again, must you get so personal??? Maybe the shoe is on the other foot? 🙂

(**) Peace. 🙂

Alex, fancy throwing in any of your clear headed logic here?

LikeLike

OK – I agree we seem to be talking past each other a little. My ‘sticking your tongue out’ comment was meant to be a bit of light banter (sorry, just my sense of humour!) 🙂

Instead of doing another long response to what you wrote, let me just try and succinctly restate what I’m saying:

The article seeks to address the question ‘What is atheism’, and Alex says towards the start “There is a direct symmetry between -ism and -ist on this view”. As I understood it, it then proceeds to unpack what this symmetry looks like, and how the symmetry may be maintained for both views ‘atheist=hard atheist’ and ‘atheist=lacktheist’. He then discusses further issue related to probability etc. [may be Alex is the only one who can say if this is fair]

My point, in response, is that this is actually a discussion of terminology. We must look at how the suffixs ‘ism’ and ‘ist’ are defined and used; and as you correctly stated we must look at how the prefix ‘a’ is defined and used. This seems to me to be the core issue; Whether or not the burden of proof is greater for one or other position is irrelevant – this is not definition-ally connected to the terms. So we must seek to dispassionately assess the terminology. (for your interest – I am a theist who used to think atheist=lacktheist was a legitimate position until reading this article).

So, let’s start with the prefix ‘a’. You’re correct that it means ‘without’. So what does this do to the word ‘atheism’? It seems to me like it could legitimately mean either sense – ‘without theism’ (i.e. ‘lacktheism’) or ‘without God’ (i.e. ‘hard atheism’) – Theos just being the Greek word for God. So, to consider which of these we should favour we should look at the suffix ‘ism’. At dicitonary.com we have – “used as a productive suffix in the formation of nouns denoting… doctrines”, which is similar to other definitions. From this definition, we should favour atheism meaning the doctrine there is no God, because ‘not-theism’ isn’t a noun. It just means not ‘theism’. Of course, you could just say ‘atheism is just not-theism’ but then it is not anything, it means all your saying is ‘not theism is just not theism’.