0. Introduction

Recently I wrote a blog post about different ways of thinking about the definition of the terms ‘atheism’ and ‘atheist’. I was interested in the relation between belief and degrees of belief. Does lacking a belief mean lacking all degree of belief? To me, it seemed like the answer was ‘no’; one can lack a belief that p, yet still have some small degree of belief that p. That was how I describe my own internal doxastic state with regards to the proposition that no gods exist. I don’t feel like it is correct to say that I believe that no gods exist, but I have a small degree of belief that they don’t.

Part of my reasoning behind why I am only slightly in one direction rather than the other is because it is a proposition in metaphysics, and this seems like the most one can ever really have about such propositions. For example, it seems at least conceptually possible that there exists some god who is entirely unverifiable, some sort of deist god who never intervenes in the world and has left no trace of his existence for us to find. How could I ever know if such a god existed? Obviously, I couldn’t. But this type of god would also be the sort of thing that I couldn’t get any information about at all, either for or against. For this type of thing, there couldn’t be any evidence, and so one can never be confident that it doesn’t exist. So while I have an intuition or feeling that they probably don’t exist, it is not strong – after all, I don’t think that I know what the world is like at the most fundamental lever, so I don’t place much weight in what my pre-theoretical intuitions about that sort of thing say. They do lead me in one direction, but only slightly. That’s my view anyway. (An interventionist god who cares about human suffering seems far less likely to me than this epistemologically inaccessible god, and I would have a far lower degree of belief in such a personal god).

So I would say that my degree of belief that there are no gods is more than 0.5, but not much more. It seems to me that this doesn’t qualify as a strong enough belief for saying “I believe that there are no gods”. To me, saying that requires a higher degree of belief than I have. It is a declaration of a certain level of commitment to something to say “I believe that p”, and while it is not saying that you are utterly convinced that p, it is saying more than that you are minimally convinced; belief means something like ‘somewhat convinced’. I’m not sure that there is a precise numerical value which is the cut-off point between non-belief and belief; certainly not for all possible circumstances anyway. However, I just feel like my degree of belief is not strong enough to qualify in this context.

This is just like a situation where you may feel quite sure that a given person has not enough hair to count as hirsute, even though you are not sure whether there really is a precise number of hairs that one has to have in order to count as hirsute, or if so what that number of hairs is. Yet you just feel quite sure that this amount of hair isn’t enough. That’s how I feel about the god proposition.

Before getting to that point though, I spent some time explaining how there is some controversy about the definition of ‘atheist’, and this caused a bit of discussion on the comments below my past blog post on this – quite a lot longer than the actual article itself (and is still continuing as I write this), where people continued to discuss how they saw the right and wrong ways to define ‘atheist’.

My main point in the first section of that post was actually to argue that what seemed like a significant discussion between the atheist and theist is actually just a trivial definitional exercise on which nothing of any significance hangs. By this, I mean that it doesn’t matter if people disagree about whether someone should be called an atheist, a lacktheist or a hard-atheist, etc. The doxastic stance that the person holds, and any burden of evidence that comes with it, is what is actually important, and it remains the same regardless of what definition is used for the terms involved. We should just agree on a definition at the start of the argument and then move on into the interesting stuff.

Here I want to make that point as clearly as possible. So I will visualise a set of related positions – not a comprehensive list, but a reasonably thorough and precise list – so that we can see clearly what the different definitional positions are. I also want to express how this area is actually surprisingly rich from a logical point of view, and the various combinations of positions makes for an interesting enough landscape to categorise as a purely academic exercise. However, once we have a good grasp of the different definitions we could plausibly have in mind (the ‘landscape’), we can see how a particular person’s view gets classified. As we shall see, on some views I am an atheist, on some I am an agnostic atheist. The ability to translate between the different schemes considered provides the potential for more than just an academic classification exercise. It suggests the ability to help people stop talking past one another by providing a precise translation manual. All too often people hold different but not clearly articulated ideas about what it means to be an ‘atheist’ or ‘agnostic’ when they are in discussion and hopefully by setting out the landscape clearly we can be of some help here.

- Degree of belief

First, let’s consider the scale of belief about some proposition p (which will remain fixed as ‘some god exists’. The scale ranges from 0 for absolute conviction that p is false, to 1 for absolute conviction that p is true, with 0.5 being the middle point:

We can consider, for some agent a which we will keep fixed, that there are various propositions about a‘s beliefs and knowledge claims that we are interested in:

- Bp = a believes that p

- B~p = a believes that not-p

- ~Bp = it is not the case that a believes that p

- ~B~p = it is not the case that a believes that not-p

- Kp = a knows that p

- K~p = a knows that not-p

- ~Kp = it is not the case that a knows that p

- ~K~p = it is not the case that a knows that not-p

We will track where these propositions go under the belief scale, and then move on to add labels for various positions in as well.

2. Visualisations

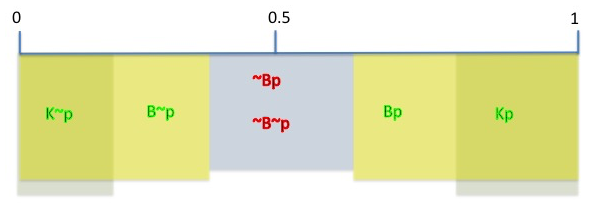

Although the pair p and ~p are dichotomous (so that ‘p v ~p‘ is a tautology), this is obviously not the case for Bp and B~p; it is quite possible for neither of them to be true. Our agent might not believe that Kuala Lumpur is the capital of Malaysia, and might not believe that Kuala Lumpur is not the capital of Malaysia. The same goes for Kp and K~p. This leaves room in the middle for a ‘belief-gap’. We will visualise this on our belief scale with a penumbra (or grey area) in which they a neither believes p nor believes that not-p. We could add this to our diagram as a shaded area underneath the section of the range to which it applies:

So in the diagram above, the grey area (the penumbra) extends beyond 0.5 degree of belief to some extent in either direction. This reflects that someone could have a degree of belief which is (say) 0.51 that p but that this would not be enough for it to be true that “a believes that p“. For that to be true, a‘s degree of belief has to be greater than this. Precisely how much greater is vague and impossible to give a precise number to. All that we can (or need to) say is that for a to believe that p, their degree of belief has to be greater than the extent of the penumbra.

On either side of the penumbra, we would find the regions in which a holds a positive belief, either that p or that ~p:

We can add in knowledge claims here as well, where as we go along the scale towards 1 (or 0), we get to some (vague and impossible to make precise) point at which a doesn’t just believe that p (not-p), but knows that p (not-p):

So our fully annotated diagram of the situation looks like this:

Given what I outlined in the last post on this topic, I sit just to the left of 0.5 on this scale (where p is ‘some god exists’). The green line is me:

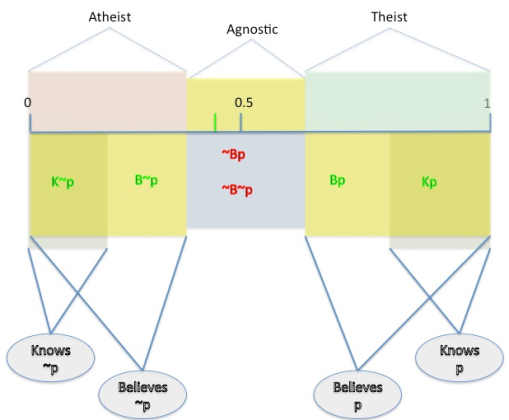

It seems like my degree of belief is such that I don’t believe that p and I don’t believe that not-p. All this is rather uncontroversial*. The controversy, what there is of it, comes in when we decide which labels to apply to which position on the scale. We will do this by adding shaded areas to the top of the diagram. The first proposal we will consider (call it View 1) is where a ‘theist’ is someone who believes that p and an ‘atheist’ is someone who believes that not-p, which makes an ‘atheist’ a ‘hard-atheist’:

This has the consequence that theist/atheist is not an exhaustive distinction; it is possible to be in the area not covered by either (which is where I sit on this diagram). I am not an atheist on this picture (I am unclassified on this picture).

We might want to say that there is no such area, and that everyone is either a theist or an atheist. This sort of line has been put to me in the past. The idea is that if you act as if there is no god, then this makes you an atheist. Actions, it might be thought, are binary, in that you either act like you believe in a god (by going to church, praying, etc), or you act as if there is no god (by not going to church, praying, etc). This may make us think that everyone’s actions either make them an atheist or a theist (depending on how plausible we find this reasoning), in which case there should be no gap between the two positions on our scale (call this View 2):

On this view, a theist is not necessarily someone who ‘believes that p‘, but is just someone whose degree of belief that p is greater than their degree of belief that not-p. Similarly for the definition of ‘atheist’. I would count as an atheist on this view, even though I don’t believe that not-p. I count as an atheist just because my degree of belief that p is slightly less than 0.5. The definition of ‘atheist’ on this view is neither the same as ‘hard-atheist’ nor ‘lacktheist’.

As another option (call it View 3), we could think of the theist/atheist distinction as exhaustive, but draw the line between them on the point at which we switch from not believing that p to believing that p. This would make the definition of ‘atheist’ that of the ‘lacktheist’:

On this view, I count as an atheist, and interestingly so would someone whose degree of belief that p was on the positive side of 0.5 but still in the penumbra; the sort of person who would say that they have a very weak degree of belief that some god exists, but not enough for them to say ‘I believe that some god exists’. That person would count as an atheist on this view.

We might think that the term ‘agnostic’ comes in here somewhere, and that it should come in to fill the gap between theist and atheist on View 1, like this (call it View 1.1):

On this picture, an atheist is someone who believes that not-p, a theist is someone who believes that p, and an agnostic is someone who does not believe either of p or not-p. On this picture, I come under the agnostic category, and not the atheist category.

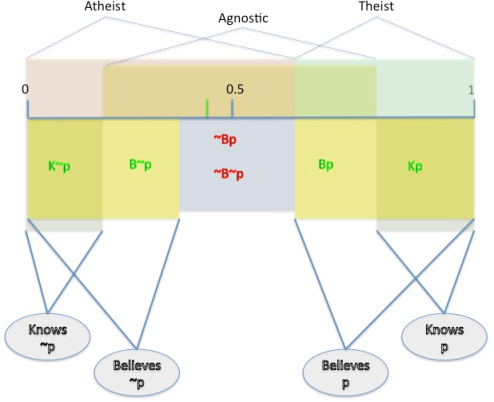

We could add this version of agnostic (i.e. someone who does not believe either p or not-p) to View 2, to make View 2.1, as follows:

On View 2.1, all agnostics are also either atheists or theists; nobody is just an agnostic. On this view, I am an atheist and an agnostic.

Continuing the series, we could include the agnostic in the diagram and have ‘atheist’ pictured as a lacktheist (View 3), resulting in View 3.1, like this:

On this view, I would count as an atheist and an agnostic. On this view all agnostics are also atheists; there are no pure agnostics or agnostic theists.

However, one might think that the term ‘agnostic’ does not relate to a lack of belief but instead to lack of knowledge; it means that you don’t know if p is true, or if not-p is true. If that were the case (View 1.2), we would want to draw the agnostic area as follows:

On this view, there are ‘pure’ agnostics (and I would be one), but there are also agnostic atheists and agnostic theists (in contrast to View 1.1).

If we add this notion of agnosticism to Veiw 2, then we get View 2.2:

In this view, everyone is either an atheist or a theist (there are no pure agnostics) and there can be both agnostic atheists and agnostic theists. This only differs from View 1.1 in that the definition of agnostic is tied to knowledge, not belief.

Lastly, for completeness, I will consider View 3.2, which combines this agnosticism with the lacktheism of View 3:

On this view, an atheist is a lacktheist, and there can be agnostic atheists and agnostic theists. I am an agnostic atheist on this view.

Here are all 9 of the views for comparison:

3. Logical relationships

We have 9 views outlined above (View 1, 1.1 & 1.2; View 2, 2.1 & 2.3; and View 3, 3.1 & 3.2), but what are the relationships and differences between them? Here is an incomplete table showing some of the various properties of the different views and how they differ from one another:

Each view is unique in some respect or another. The difference between View 1.1 and View 1.2 (for example) is just whether agnostic means not believing either way that p or not knowing either way that p. This difference decides whether there are agnostic atheists/theists or not.

According to that summary, I am an there are two views according to which I am antheist, one according to which I am an agnostic, four according to which I am agnostic atheist, with one where I am not classified. It is noteworthy how many different classifications one and the same doxastic attitude can come under. No wonder there is often confusion as to the usage of the terms involved.

4. Motivations

What we have is a landscape of different definitions and their various combinations. These are just the combinations I could see as being remotely justified. Each combination has something which backs it up conceptually.

- There seem to be decent reasons for thinking about atheism and theism as being dependent on believing p and on believing not-p, which is the characteristic of View 1, 1.1 and 1.2.

- However, the idea that belief is tied to action, and is thus binary, gives rise to the motivation for View 2, 2.1 and 2.2.

- Then again, the definition of atheism as ‘lacktheism’ is clearly very popular among contemporary atheists, and this motivates View 3, 3.1 and 3.2.

- There also seems to be some intuitive support for the idea that agnosticism simply fills in the space between atheism and theism, such that everyone is either an atheist, and agnostic or a theist (with no overlap), which informs View 1.1.

- While this view of agnosticism seems fairly intuitive here, there is also something to be said for modelling agnosticism as relating to knowledge. Thomas Huxley, the person who coined the term ‘agnostic’, seems to have this association in mind when he said the following:

Agnosticism is of the essence of science, whether ancient or modern. It simply means that a man shall not say he knows or believes that which he has no scientific grounds for professing to know or believe.

Thus, there is a sort of exigetical support for the idea that agnosticism is epistemic rather than doxastic (i.e. about knowledge rather than just belief). If that is motivational for you, then you may be drawn to thinking of agnosticism as in View 1.2, 2.2 and 3.2.

5. Conclusion

It seems like a simple question, so often gone over, but so rarely gone over methodically:

What does ‘atheist’ mean?

But it has a surprisingly large number of potential, plausible-looking combinations of positions on the table. The benefit of classifying the various possible logical combinations is that we can translate between people’s usages. Here’s how:

First, one needs to assess internally what their level of belief is in the proposition being considered. Decide as best you can what your degree of belief is. Next also try to decide what you think (roughly) the thresholds are for belief and knowledge. Test yourself. For example, if you feel quite confident that you believe that p, do you also feel like you know that p? If not, then you believe without knowledge, and so you are in the middle section, etc.

In this way, we can get a feel for which region in the bottom part of the diagrams you fit into without too much need to quantify your degree of belief precisely. All you have to do is find which region of the belief scale you fit on. Once you have this in place, you can see how you are classified according to the various views. I did this in this post, and showed my results. So if someone asks me if I’m an atheist, I think my reply will now be ‘I’m an agnostic atheist on most definitions of the key terms, but on some of them I am an atheist’. This qualification doesn’t mean that I am changing my mind about what I believe, or trying to dodge any burden of proof for my claim. All the different views indicate is different ways of describing the same thing.

There is no such thing as the ‘correct’ definition of what an atheist is. There is no such thing as the ‘correct’ definition of anything. Definitions are all arbitrary. One can use a definition in a way that fits the practices of a language using community, but other than ‘fitting in’ there is nothing else to decide whether a definition is correct or not. So there shouldn’t be a debate about what the definitions mean, from a logical point of view. We should only be interested in what people actually believe, and why.

There may be a larger political issue about the definition of ‘atheist’ due to the idea of an ‘atheist community’, but this is an issue I am not interested in. If I don’t classify as atheist enough for the atheist community, then so be it. I’m not going to change my sincerely held views just to be part of a club, and any club which is defined in terms of belief which requires people to adopt beliefs merely for the purposes of joining seems like an inherently contradictory institution.

It may be that people hold that the definitional game is more significant that I think it is for the following reason. It may be that when one joins a religion (or a new church, etc), that one sort of fits their beliefs to the community. As if someone says to themselves, ‘Now I’m part of the Calvinist community, I better figure out what beliefs I have’. This would make the beliefs follow from the belonging to a group. For all I know, this is how people view beliefs, and are happy to let themselves hold beliefs just because they are told that ‘people like us believe in such and such’. To me though, this gets the direction of travel the wrong way. First you have to have certain beliefs, and it is only because you antecedently do (or do not) hold whatever beliefs you do that you qualify for belonging to a club that is defined by beliefs. So one should say something like ‘I believe in the doctrine of predestination and original sin (etc), so I better figure out which group I belong to’. For me, beliefs come first, and labels (such as ‘Calvinist’ or ‘atheist’) follow after.

*From here on out, I will assume this basic picture to be correct. One could argue that the penumbra could really just apply to the 0.5 point and extend no distance in either direction. Even if you do so, this would still mean that the grey area has some extension. The reader should feel free to imagine the grey area being larger or smaller if they so wish if they disagree with the extent I have given it above. It should be agreed by all parties that there is some penumbra, even if it only apples to 0.5 and nowhere else.

One of the issues is that, despite the definition, discussions are almost always between those who believe personal gods don’t exist and those who believe a personal god does exist. If we could all agree to leave out deistic beliefs that few people hold (and those who do hold to a deistic view of the world rarely argue in favor of their view) and focus on discussing whether a personal god does or doesn’t exist, it would make things much easier with regards to definitions. For many, the degree of belief that personal gods do not exist is far stronger than the degree of belief that non-interventionist gods don’t exist.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I like the thoroughness and clarity of your presentation. I also think JD Kain makes a good point as regards the GDC. One would first have to indentify the god in question in order to make the most of your system of taxonomy. (I think you mentioned as much, but it was more in passing.)

The beauty of your system is that it could be used for any idea/notion/concept/-ism/-ist in order to clarify one’s level of belief/knowing.

In one sense, it could be considered trivial, but in the context of discussions and debates about difficult topics, it could be very helpful–which seems to be the reason you wrote the article.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nice post, Alex, thank you. I have some questions and criticisms.

In your definitions you don’t allow for any overlap between atheist and theist, which makes sense. You also don’t allow for a “middle ground” of belief, as you require that either a believes in p, or a lacks a belief in p (i.e., Bp and ~Bp are exhaustive and exclusive, and likewise for B~p and ~B~p), and this also makes sense.

Even though it’s not explicit in the diagrams, ~Bp (lacktheism) should span from 0 through the right side of the penumbra, while ~B~p (“lack-atheism”??) should span from the left side of the penumbra through 1.

Now, the penumbra is the intersection ~Bp ^ ~B~p, just as you’ve defined it. However, it can also be written as:

(1) Penumbra = ~Bp \ B~p, or

(2) Penumbra = ~B~p \ Bp.

But this admits two different interpretations: (1) could be interpreted as meaning “weak atheism” while (2) could be interpreted as “weak theism,” yet they’re one and the same region.

So how would you resolve these two different interpretations of the penumbra?

Views 2.x, for example, allow for someone to be a theist while being in the state of ~Bp (when the degree of belief is between 0.5 and the right side of the penumbra). This I find counter-intuitive: how can a be a theist when a doesn’t believe p = “some god exists”? The left side of the penumbra is not as counter-intuitive to me (other than the contrivance of the double negation); I can think of a as an atheist while a does not believe that no gods exist, as this does not entail belief in p, even though it is entailed by a belief in p.

In fact, there’s an asymmetry between beliefs and non-beliefs: Beliefs entail certain non-beliefs, whereas non-beliefs entail nothing (i.e., nothing that’s non-trivial, like they’re not their negation):

(3) Bp ==> ~B~p

(4) B~p ==> ~Bp

(5) ~Bp ==> nothing

(6) ~B~p ==> nothing

To me, it seems that the “lacks of belief” should not be interpreted as theism of any type (“weak” or not), so that the interpretation of the penumbra in (2) should be discarded, while the interpretation in (1) should be allowed (though not necessarily adhered to). For this reason, I would discard Views 2.x.

Another possibility would be, like you suggested, to shrink the penumbra to a point at 0.5. This would rescue Views 2.x, and break the symmetry between beliefs and lacks of belief above by collapsing the implications into equalities (double implications). In this case, there would be no middle-ground between B~p and Bp (except possibly for one point, like you suggested). However, this seems counter-intuitive also, because it seems that there should be plenty of room (more than just one point) for not holding a belief while not being committed to the contrary.

Views 1.x avoid this problem altogether by defining both atheist and theist as “strong” in the sense of excluding the intersection of lacks of belief (the penumbra). I think this is an allowed definition, although I personally wouldn’t subscribe to it.

Views 3.x also avoid this problem by allowing the definition of atheist to encompass the lacks of belief (the penumbra). This is allowed also, and it’s the definition that I would subscribe to.

As for the “agnostic” part, I would argue that it should refer to knowledge instead of to belief, because otherwise I don’t see the point of distinguishing between knowledge and belief. However, I know that “agnostic” is often used as a wishy-washy middle ground of belief, so it should be, of course, allowed when referring to the penumbra in Views x.1. I would prefer the other views where agnostic spans all the area outside knowledge (i.e., exclusive of K~p, Kp). (In fact, I may even argue that K~p and Kp should be points at 0 and 1 respetively, but that’s another conversation.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmmmm….agnosticism is tricky isn’t it, because ‘knowledge’ is not well defined. If we go with ‘justified true belief’ (even though that has been shown to be incorrect) then someone who claims they ‘do not know if god exists’ is either saying they don’t feel justified to believe he exists or they don’t know if it is true. But this seems the same as saying they ‘lack belief about god’, so what does it add?

The quote you gave from Huxley – ‘Agnosticism is of the essence of science, whether ancient or modern. It simply means that a man shall not say he knows or believes that which he has no scientific grounds for professing to know or believe.’. This is stronger than saying ‘I don’t know if god exists’, it’s saying something like – ‘only believe what there is scientific evidence to believe’. But this is only loosely connected to the lack of belief that god exists, because the following states are possible:

1) non-agnostic atheist (a): Someone does not ‘only believe on scientific evidence’, and thinks there is scientific evidence for there being no god, and believes there is no god

2) non-agnostic atheist (b): Someone does not ‘only believe on scientific evidence’, and thinks there is no scientific evidence for there being no god, but believes there is no god

3) agnostic atheist (a): Someone does ‘only believe on scientific evidence’, and thinks there is scientific evidence for there being no god, so beleives that gods exist

4) agnostic atheist (b): Someone does ‘only believe on scientific evidence’, and thinks there is no scientific evidence for god, so does not believe god exists

5) agnostic theist: Someone does ‘only believe on scientific evidence’, and thinks there is scientific evidence for there being gods, so believes gods exist

6) non-agnostic theist (a): Someone does not ‘only believe on scientific evidence’, but thinks there is scientific evidence for gods anyway, and believes god exists

7) non-agnostic theist (b): Someone does not ‘only believe on scientific evidence’ and thinks there is no scientific evidence for gods, but believe god exists anyway

Complicated! However, this has less to do with belief/lack of belief, it is rather about the method used to get to belief about god. Surely it sits over and above the atheist-theist line, not in the middle of the line?

Other people seem to use ‘agnostic’ to mean something even stronger – ‘it is impossible to know whether gods exist or not’. This, therefore, leads explicitly to a lack of belief that god exists, but equally a lack of belief that god doesn’t exists. This is an forth position that is a subset of the 3rd as follows:

1) atheist – god doesn’t exist

2) theist – god does exist

3a) no belief about god

3b) no belief about god because agnostic – it is impossible to know

LikeLike

You say:

“This I find counter-intuitive: how can a be a theist when a doesn’t believe p = “some god exists”?”

In a definition-based sense, you’re likely right. But in an ethnographic sense this is far more plausible. For instance, religious children are raised to parrot statements before they can credibly assert Bp, but they never really ~Bp, it’s just that the belief is in its infancy.

So too with partially ‘church-ed’ people, they may come to services, sing songs, attend barbeques etc. Maybe they’ve always had an inkling, an admiration but it’s never been developed far enough to be ~Bp or B~p because it’s existed as a fuzzy possibility in their lives, or they’ve been culturally a believer (Christmas, Easter, funerals, weddings, maybe a baptism here or there).

While I don’t expect this to impress based on your really good grasp – I think that there are people who have a poorly examined, wishful thinking that leans in the direction of theism which would become more readily graspable if you put before them a specific god or gods rather than ‘some’ god.

LikeLike

From the five minute mark Dr. Josh Rasmussen says that there are some people who think there’s some evidence for X to exist but lack a belief that X exists. Perhaps this is both slightly counter-intuitive, but also true?

LikeLike

Yes, but I don’t think it is counterintuitive. In a murder trial, each side will provide evidence, both for and against, but you don’t just accept that the accused is both guilty and not guilty. You weigh the evidence for and the evidence against. If you end up acquitting, that doesn’t mean there is no evidence that they were guilty, it just means that it was oughtweighed by the evidence for.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Evidence can be of poor quality and insufficient to warrant holding a belief (being convinced). For example, there’s evidence for the existence of the Loch Ness monster such as grainy, ambiguous photos, anecdotes of inn-keepers who own motels near Loch Ness, and the like. The question is whether the evidence is of sufficiently good quality to justify belief in such an extraordinary claim. Many people find the evidence unconvincing and don’t hold a belief in the existence of the Loch Ness monster. Evidence and lack of belief can justifiably coexist.

LikeLike

Thank you for your response. You say:

“In a definition-based sense, you’re likely right. But in an ethnographic sense this is far more plausible.”

– This article and ensuing discussion are all about definitions. If, by “ethnographic sense” you mean customs or cultural labels, that is not, as I see it, the subject of this discussion, which deals in definitions relating to beliefs or lack of belief that people actually hold. I suppose you could always define “theist” as someone who is culturally labeled that way, regardless of their actual beliefs or convictions, but that would be a different discussion from the one here.

“[R]eligious children are raised to parrot statements before they can credibly assert Bp, but they never really ~Bp, it’s just that the belief is in its infancy.”

– If by parroting statements you mean repeating them without thinking, that does not entail that the person doing the parroting actually believes what they’re parroting. One can parrot a statement without believing it. Also, one can assert a belief without actually holding the belief. People do lie. Moreover, one can even “credibly assert” a belief without actually holding the belief itself. For the assertion to be “credible” all that’s required is that someone else believe my assertion that I believe something, or that it may seem reasonable that I believe something, not that I actually believe it. People can lie and deceive. It’s important not to conflate actual beliefs with expressions of belief.

– I’m not entirely certain what you mean by a child’s belief being in its “infancy.” If you mean that the belief is just beginning or starting out, that would still make it a belief. If you mean that young children are cognitively incapable of holding the particular beliefs (or lack thereof) that we’re referring to here (namely beliefs in the existence of gods), then that would not fit the definition of the agent “a” that we’re talking about in this entire thread. If you read this thread, you may recall that “a” is defined as a reasoning agent capable of holding or not holding belief in a god or gods, and that would exclude very young children. For example, a rock doesn’t hold any beliefs, but it is not considered an “atheist” or any kind of “ist” subscribing to any kind of “ism” precisely because it lacks the reasoning agency required to be a “fill-in-the-blank-ist” subscribing to a “fill-in-the-blank-ism.” As a more concrete example, an infant born to Muslim parents may be “ethnographically” labeled “Muslim” yet it holds no beliefs in gods because it’s cognitively incapable of doing so. According to the definitions in this discussion, that child would not be a Muslim (or any kind of theist for that matter) until it is cognitively equipped to hold or reject such beliefs. That child would be neither a theist nor an atheist because it lacks the required reasoning agency to be either.

“So too with partially ‘church-ed’ people, they may come to services, sing songs, attend barbeques etc. Maybe they’ve always had an inkling, an admiration but it’s never been developed far enough to be ~Bp or B~p because it’s existed as a fuzzy possibility in their lives, or they’ve been culturally a believer (Christmas, Easter, funerals, weddings, maybe a baptism here or there).”

– Participating in religious rituals does not entail that a person actually believes in gods or supernatural agents. One can participate in religious rituals while being an atheist. That’s what it means when people say “I’m Catholic by tradition, but I don’t believe in God,” or “I am a cultural Jew but I am an atheist (aka a secular Jew).” These are people who celebrate religious holidays, attend religious services on special occasions or even regularly, repeat certain sayings and songs, eat certain foods on certain days, enjoy the sense of community and tradition of religious rituals etc. and go through the motions but don’t hold supernatural beliefs. As a more concrete example, many people here in the U.S. celebrate Halloween without actually believing in the existence of ghosts, ghouls and vampires. It’s important to keep this distinction separate. This is what the “ethnographic” labels miss.

– As to “inklings,” “admirations,” and “cultural beliefs,” none of these entail actual beliefs that people hold. As to “fuzzy possibilities,” one can admit that something is possible without believing that it is true or that it exists. For example, if you show me an urn full of marbles, I will readily admit that it is possible that the number of marbles in the urn is “even” without actually believing (being convinced) that it is even until I’m shown evidence that it is even (like actually counting the marbles or weighing the urn with and without the marbles, etc.).

“[T]here are people who have a poorly examined, wishful thinking that leans in the direction of theism which would become more readily graspable if you put before them a specific god or gods rather than ‘some’ god.”

– A “poorly examined” belief is still a belief, is it not? Beliefs can arise for good reasons or for poor reasons, and they may or may not reflect reality independent of those reasons, but they are still beliefs. Wishful thinking is a fallacy (ad consequentiam), which means it is a bad reason to hold a belief (although the content of the belief itself may be true or false independent of the reason that led to that belief).

– I’m not sure what you mean by “leaning in the direction of theism.” Either one holds a belief (is convinced) that at least one god exists or one does not hold such a belief. Accepting that something is possible, or being open minded about its possibility, is not the same as actually holding the belief (being convinced) that it is true. It is possible that the coin landed “tails” but I am not necessarily committed to believing (being convinced) that it landed tails just because I accept that it is entirely possible. As to the “specific” vs. “some” god, this is a distinction without a difference here because belief in a specific god entails belief in some god, and believing that it is not the case that “some god exists” entails not believing in the existence of any specific god.

A person’s actual belief or conviction is separate and distinct from outward expressions or professions of beliefs, or cultural customs, and I think it is useful to keep them separate. This distinction is not captured by “ethnographic” labels. A secular Jew or a traditional Catholic can both be atheists.

LikeLike

Above, I meant “break the asymmetry” or, better yet “restore the symmetry.”

Finally, my preferred View would be 3.2.

LikeLike

Hi Alex and autonomousreason… firstly, thanks for all the discussion this previous week, I have really enjoyed the back and forth (even if I got frustrated at times!). I love having things like this simmer in my brain. My conversation with autonomousreason particularly helped me think more clearly and sharpen what I was saying.

It got to a point in the discussion with autonomousreason where I really wanted to send diagrams and didn’t know how, so instead I decided to summarize my points on the following blog:

https://brainsimmer.wordpress.com/

I am not a blogger, so currently don’t intend to share this with anyone else, but would appreciate any comments/criticisms you have, or anything you think I’ve said incorrectly.

Thanks again!

LikeLike

“I am not a blogger”. I think you are a blogger. I hereby define the word ‘blogger’ to mean a person with a blog. You have a blog. Ergo, you are a blogger 🙂

LikeLike

Ha ha! Ok 🙂

I blog, therefore I am

LikeLike

Look at you, a blogger! 🙂

I read your blog, but couldn’t find a way to comment on it. Thank you for taking the time to put it together.

By probability I meant a proxy for degree of belief, just as Alex defined it in his second article: “What is Atheism? II”.

Alex’s second article addresses all your points (and mine) very precisely. I also made a comment on the second article which clarifies an objection that I have to the second article’s View 2.x definitions, which goes to your own concerns with the “lack of belief” intersection, or “penumbra.”

I don’t think there’s anything I could add to Alex’s second article and my comment to it. Who knows, maybe I’ll write a blog article of my own, time permitting :).

LikeLike

there should be a ‘comment’ button on the left menu at the top.

LikeLike

You don’t think there is a legitimate concern that I have raised?

I feel you have moved slightly through our discussion at least!

LikeLike

I also provided a comment on view 3 on why the probability doesn’t help

LikeLike

Two comments that relate to my post also –

Firstly, when you bring in probability I’m not sure what value the term ‘lack of belief’ has. If someone thinks god’s existence is 60% probable, they are necessarily saying his non-existence is 40% probable?

Of course we could arbitrarily define a cut-off point – all people below 40% are atheists, and above 60% are theists. But then we are not defining atheist as ‘lack of belief in god’, we are defining atheist as ‘belief that there is greater than 60% probability that god doesn’t exist’. So the first discussion on your original post as to whether atheists could be defines as ‘those who lack belief in god’ is no longer the case.

But to get round this you talk about ‘thresholds’ over which someone (presumably) commits to belief. But this also doesn’t work to preserve the lacktheist definition. View 3, which seems to be the only one that allows ‘lacktheist’ into the definition of ‘atheist’, you have missed the point below which someone is prepared to commit to the belief that god doesn’t exists. This needs to be added at the lower bounds of your ~B(p) ~B(~p) section. But then, notice, this section is completely neutral in terms of ‘commitment to belief’ either way… so why should it be included in the atheist section?

LikeLike

Oh yes, there’s a small sign saying “Leave a comment” on the top left, which I missed. I was looking for a large button at the bottom right that says “Post Comment” like there is here.

All I was going to say was thank you for posting! And to refer you to Alex’s second article which, together with my comment on that article, cover everything I would have to say in response to yours (rather than rehashing everything that’s there).

Basically, your argument is that only View 1.x is allowed. Alex argues that Views 1.x, 2.x and 3.x are all possible. I agreed with Alex that Views 1.x and 3.x are possible (although I would subscribe to View 3.2 specifically) while I criticized Views 2.x and suggested they should be discarded. Does that make sense?

LikeLike

Instead of “probability,” let’s call it “degree of belief,” per Alex’s second article, which more accurately reflects what I was trying to say.

I was suggesting degree of belief as a way of breaking the overlap in the “lack of belief” region (“penumbra” per Alex’s article), because I agree that there should be no overlap between atheism and theism. However, on further thought, I think it is nonsensical for a theist to be in the penumbra (lacking belief) while that’s not necessarily the case for the atheist.

Again, please refer to Alex’s second article and my comment to it.

LikeLike

In my opinion, view 3 has problems because it defines the penumbra as atheist when it is neutral (lack enough degree of belief either way to commit to belief)

Of course, we could divide the penumbra down the 0.5 line and say those below it are atheist, but this is just view 1.

I don’t understand the insistence to define the neutral group with a label? Why do you think that is?

It is only when thinking this through in discussion with you that I’ve clearly seen the neutral overlap (and I think that may be true for you also?), which leads me to think maybe the desire to label lack of belief as atheism is just not well thought through, but has now stuck. As humans we get so passionate about our prior commitments!

By the way – thought you may be interested in this http://departments.bloomu.edu/philosophy/pages/content/hales/articlepdf/proveanegative.pdf

LikeLike

JEJ

LikeLike

Alex and autonomousreason –

Now I have a blog I may be interested in putting up a few other things I’ve been musing related to theism/atheism. But after having these discussions with you I think that it is always good to bounce ideas with people, particularly when they have an opposing view to you, so I was wondering if you might be willing to do that for me in the future? (as in a throw an idea to you, and you critique it)

If so, go to my blog post https://brainsimmer.wordpress.com/ and hit the ‘contact’ but on the top left menu so that I can (privately) have your email address

Thanks!

LikeLike

This means YOU, personally, really should weight your words SERIOUSLY p a f, and I strongly advice you to delete this written defamation y j i g of both characters and a huge group of people who do not take slander and character assassination like this easily g k m r k. I do not know which organization you have got to back you up, but if you do not care about lawsuits in the multi-million dollar range, fine, just keep on what you are doing a g u g g. If you DO care about spending x-amounts of money to try and defend this CLEARLY written libel, then take my DELETE-advice. Your “Post” is now officially taken both copies and screen-shots of and digitally stored for later use and evidence. This is just a warning. We are antifa, we do not forget. alexis.bourquard@outlook.fr

LikeLike

Errrm. Ok. (I have no idea what you are talking about)

LikeLike